Cultivated meat, made from animal muscle cells grown in bioreactors, closely resembles conventional meat in terms of protein and amino acid composition. However, its nutritional profile depends heavily on the growth media and production process. While it replicates key nutrients like essential amino acids (leucine, lysine, methionine, etc.), differences in protein forms and digestibility remain under study.

Key points:

- Cultivated meat can match conventional meat's amino acid profile but requires precise media formulations.

- The absence of natural post-mortem processes affects flavour development and texture.

- Early versions show protein deficiencies (up to 24% lower in some amino acids) compared to conventional options.

- Innovations in growth media, such as food-grade amino acids and plant hydrolysates, are reducing costs and improving nutritional outcomes.

- Regulatory approval in the UK requires consistent production quality and nutritional equivalence.

Cultivated meat holds promise as a protein source but needs further refinement to fully replicate the nutritional and sensory qualities of conventional meat.

Towards sustainable protein production

How Cultivated Meat Compares to Conventional Meat

Essential Amino Acid Comparison: Conventional Beef vs Cultivated Meat

Essential Amino Acids: A Direct Comparison

Cultivated meat is built from the same building blocks as conventional meat - actual animal muscle cells like satellite cells or myoblasts. This means it has the potential to replicate the same essential amino acids found in traditional options like beef, chicken, or pork [4].

"Cultivated Meat aims to match the biological properties of traditional meat." - Ilse Fraeye et al., Frontiers in Nutrition [6]

A 2025 metabolomic study took a closer look, comparing conventional chicken meat with cultivated chicken cells. The researchers found 45 shared metabolites, including key compounds like adenosine and carnosine [2]. Using advanced LC-MS/MS technology, the study revealed that while the metabolic profiles of both types of meat were broadly similar, there were notable differences in certain metabolites tied to nutrient metabolism [2].

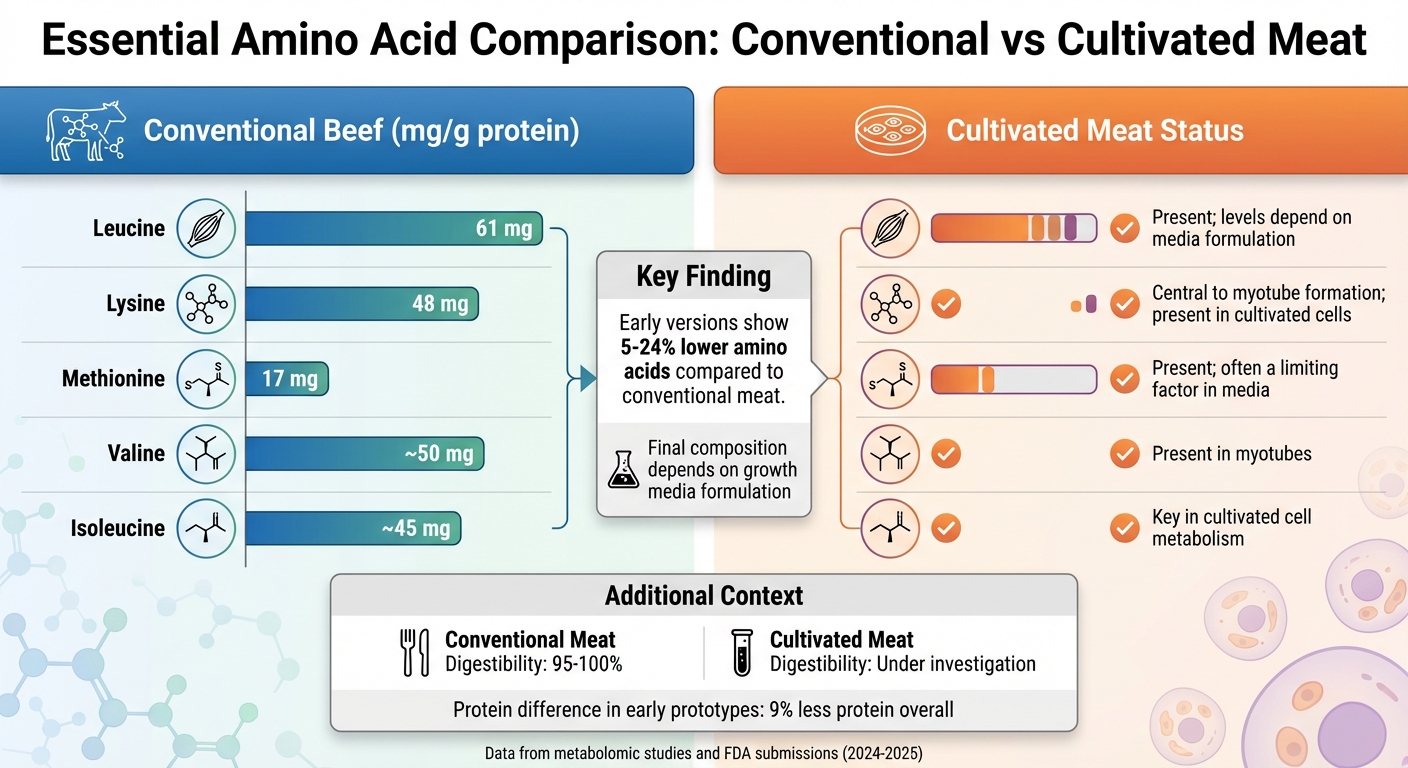

To give you an idea of the numbers, conventional beef delivers 61 mg of leucine, 48 mg of lysine, and 17 mg of methionine per gram of protein [1]. Cultivated meat can match these levels, but the exact amino acid composition depends heavily on the formulation of its growth media [1][2]. For instance, L-lysine has been identified as crucial for stabilising cellular energy (ATP) in cultivated chicken myotubes [2].

However, there is a key difference when it comes to protein isoforms. At present, cultivated muscle fibres predominantly feature embryonic or neonatal isoforms of actin and myosin, whereas conventional meat contains the adult isoforms [6]. This distinction raises questions about how cultivated meat’s proteins are digested and absorbed.

Digestibility and Absorption Rates

Conventional meat is known for its excellent digestibility, typically falling between 95% and 100% [3][4]. This makes it one of the best protein sources in terms of human nutrition, outperforming plant-based proteins, which usually range from 80% to 95% [3].

For cultivated meat, digestibility is still an area under investigation. One of the challenges lies in the maturation of muscle fibres. In living animals, muscle fibres undergo a complex development process that might not be fully replicated in a bioreactor [5]. If these fibres remain immature, it could impact both protein quality and digestibility [5][4]. The composition of the growth media also plays a significant role in these outcomes, as noted earlier.

Another factor is the lack of post-mortem metabolic changes, which in conventional meat contribute to tenderness and protein structure. These changes haven’t been fully studied or replicated in cultivated meat [5][6].

Additionally, the scaffolds used in cultivated meat production, which can make up as much as 25% of the final product, can influence its amino acid profile. For example, collagen-based scaffolds are rich in glycine, which could alter the overall balance [5][6].

While cultivated meat can theoretically match the essential amino acid profile of traditional meat, data on how well humans can absorb its nutrients is still limited [5][4]. Questions remain about how effectively vitamins and minerals added to the culture media are absorbed by the cells - and ultimately by humans [5]. The table below provides a clearer comparison of essential amino acids between the two.

Amino Acid Comparison Table

| Essential Amino Acid | Conventional Beef (mg/g protein) | Cultivated Meat Status |

|---|---|---|

| Leucine | 61 [1] | Present; levels depend on media formulation [1][2] |

| Lysine | 48 [1] | Central to myotube formation; present in cultivated cells [1][2] |

| Methionine | 17 [1] | Present; often a limiting factor in media [1] |

| Valine | ~50 | Present in myotubes [2] |

| Isoleucine | ~45 | Key in cultivated cell metabolism [2] |

Free Amino Acids and Taste

What Are Free Amino Acids?

Free amino acids (FAAs) are individual amino acids that are not bound within protein chains. These compounds play a major role in creating the "brothy" and umami flavours we associate with cooked meat, largely through the Maillard reaction - a chemical process responsible for those savoury aromas that develop when meat is cooked [8][6]. In traditional meat, FAAs form naturally during post-mortem ageing. This occurs as enzymes, like aminopeptidases, break down proteins over time, releasing flavour-enhancing compounds [8]. This is why aged beef often has a richer and more complex taste compared to fresh cuts. Specific amino acids contribute distinct flavours: glutamic and aspartic acids are known for their umami notes, while glycine, alanine, and serine add sweetness. On the other hand, isoleucine and leucine can introduce a hint of bitterness [11].

"The improvement of taste in meat flavour is due to the increase in free amino acids and peptides in meats during postmortem ageing. The former increase contributes to enhancement of brothy taste including umami, whilst the latter increase is responsible for giving mildness." - Toshihide Nishimura, Department of Food Science, Hiroshima University [8]

This natural development of flavour in traditional meat sets a high standard for cultivated meat to match. Unlike conventional meat, cultivated meat does not undergo post-mortem ageing, which is crucial for the natural formation of these flavour compounds. Processes like the conversion of glycogen to lactate or the breakdown of ATP into flavour-enhancing molecules like inosine-5'-monophosphate (IMP) simply don’t occur in the same way [6]. For instance, an electronic tongue analysis comparing cultivated mouse muscle cells with traditional beef brisket found that while the cultivated cells had a stronger umami profile, they lacked the sourness found in traditional meat [7].

Controlling Flavour in Cultivated Meat

Since cultivated meat cannot rely on natural post-mortem processes to develop flavour, producers have turned to alternative methods, particularly by modifying the growth medium. Research from January 2022 and May 2024 has shown that adjusting the medium's composition and incorporating co-culturing techniques with adipocytes can significantly impact the FAA profile, as well as triglyceride levels - both of which influence taste and juiciness [11][10].

In January 2022, a study led by Seon-Tea Joo at Gyeongsang National University used an electronic tongue system to analyse cultivated chicken and cattle cells alongside traditional meat. The results showed that cultivated meat had lower values for umami, bitterness, and sourness [11]. To address this, researchers adjusted the growth medium to increase the levels of aspartic and glutamic acids, which are critical for enhancing umami flavour.

"Unless special amino acids are added to the culture medium and taken up by the satellite cells, the amino acid composition of cultured meat will not be similar to that of TM, and eventually, the cultured meat will exhibit a different taste sensation compared to TM." - Seon-Tea Joo, Researcher [11]

Further advancements came in May 2024, when researchers from Shandong Agricultural University and Huazhong Agricultural University demonstrated how changes in insulin levels within a 3D hydrogel culture medium could manipulate triglyceride levels in cultivated chicken. By increasing fat content to two or three times that of conventional chicken, they were able to influence both taste and juiciness [10]. Producers are also testing the addition of specific additives, such as lipids or acetic acid, to better mimic the volatile flavour compounds found in traditional meat [6].

sbb-itb-c323ed3

Meeting Nutritional Standards and Regulations

Matching Nutritional Expectations

For cultivated meat to make its way to UK consumers, it must meet the same nutritional benchmarks as conventional meat. Specifically, this means proving that its amino acid profile matches - or surpasses - that of traditional meat sources [14][4].

In 2024, a re-evaluation of data submitted by UPSIDE Foods to the FDA revealed some gaps. Their serum-free cultivated chicken was found to have 9% less protein overall. Additionally, it showed deficiencies in indispensable amino acids, ranging from 5% to 24% lower compared to conventional chicken breast [14]. These shortfalls included several key amino acids essential for a balanced diet [14].

"Consumers may perceive cultured meat as equivalent to conventional products; therefore, any differences in the nutritional profile should be clearly communicated." - Dominika Sikora and Piotr Rzymski, Journal of Food Composition and Analysis [14]

The root of this issue lies in the cells' complete dependence on their growth media [12][4]. Conventional meat, despite making up only 7% of global food mass, contributes 21% of protein intake and over half of the world's vitamin B12 consumption [4]. This sets a high standard for cultivated meat to meet in terms of nutritional value.

Such challenges highlight the importance of thorough regulatory oversight, as explored below.

Regulatory Approval and Testing

Resolving nutritional gaps is a key step in gaining regulatory approval. In the UK, cultivated meat is governed by the Novel Foods Regulation (EU 2015/2283), which mandates a rigorous safety assessment before it can be sold [12][13]. The Food Standards Agency (FSA) requires detailed protein profiling to ensure nutritional safety and assess any potential allergenic risks [12].

"A detailed composition and protein analysis such as understanding the protein sequences, the protein quality and fractions of this product may be needed to alleviate any concerns alongside allergy studies." - Food Standards Agency [12]

To aid this process, the UK government has allocated £1.6 million to the FSA and Food Standards Scotland for a "regulatory sandbox" programme. Running from February 2025 to February 2027, this initiative involves companies like Mosa Meat, Hoxton Farms, and Gourmey, with the goal of developing clear technical guidance on nutrition and safety requirements for cultivated meat [13][15]. The programme will outline the specific data - such as amino acid profiling across multiple production batches - needed for novel food applications.

Consistency between production batches is a critical factor. Studies have shown that nutrient levels can vary significantly between different production lots, making standardised testing a necessity for regulatory compliance [14]. Producers must also confirm that cells have properly differentiated into muscle fibres with the expected protein composition. Techniques like genetic biomarkers and fluorescent imaging are often used to verify these attributes [12][5].

Improving Amino Acid Profiles in Cultivated Meat

Better Growth Media for Amino Acid Production

Growth media account for over half of the operating costs in cultivated meat production, with amino acids being one of the largest expenses [17]. To tackle this, producers are turning to spent media analysis (SMA). This method tracks how amino acids like arginine, isoleucine, leucine, and methionine are consumed, allowing for precise adjustments. The result? Less waste and a better balance of nutrients for cell growth.

One major cost-saving shift has been the move from pharmaceutical-grade to food-grade amino acids. This change slashes basal media costs by around 77% [17]. A great example is food-grade L-glutamine, which costs £78 per kilogram compared to £774 for reagent-grade - about a 90% saving [17]. According to the Good Food Institute, these changes could bring amino acid costs down to under £4 per kilogram of cultivated meat, a big drop from earlier estimates of £14–£15 per kilogram [9]. These savings open the door to further refining protein profiles for cultivated meat.

Producers are also exploring plant hydrolysates - derived from crops like soybeans and chickpeas - as cheaper alternatives to fermentation-based amino acids. In 2024, Believer Meats showed it’s possible to produce serum-free medium for just $0.63 per litre by replacing expensive albumin and optimising nutrient levels [17]. Similarly, BioBetter is leveraging tobacco plants to produce growth factors at a projected cost of $1 per gram, a fraction of traditional production costs [17].

"It is crucial for every cultured meat company to work on an efficient basal media formulation that shows or enables good growth performance and is cost‑efficient, as they will need it in huge amounts as soon as they scale up." - Dr. Florian Geyer, Product Manager for Cell Culture Media, Merck Life Science [16]

Tailoring Protein for Different Diets

With cost-efficient media formulations in place, producers are now focusing on customising amino acid profiles to cater to specific nutritional needs. In May 2024, researchers from Shandong Agricultural University and Huazhong Agricultural University demonstrated a method for creating "tunable" meat. By activating the MyoD gene and adjusting insulin levels in 3D hydrogel scaffolds, they were able to produce cultivated chicken with fat levels 200–300% higher than traditional chicken [10]. This innovation opens up possibilities for products designed for a variety of dietary preferences.

"A compelling advantage of cultured meat is that its texture, flavour and nutritional content can be tailored during production." - Gyuhyung Jin and Xiaoping Bao, Purdue University [10]

Cultivated meat can also be enriched with bioactive compounds like creatine, carnitine, and taurine - nutrients often missing in plant-based alternatives but vital for athletes and those on specialised diets [4]. By supplementing growth media or using co-culture techniques with different cell types, producers can craft products tailored to meet these specific dietary requirements.

Conclusion

Cultivated Meat is emerging as a protein source that can rival, and in some cases surpass, traditional meat in nutritional value. Developed from real animal muscle cells, it replicates the essential amino acid profile that gives conventional meat its dietary importance [4][6]. While early versions show some differences in protein isoforms and require added bioactive compounds like creatine and taurine, advancements in tailored growth media are enabling producers to fine-tune its nutritional content to meet specific dietary requirements [4][6].

"Cultured meat aspires to be biologically equivalent to traditional meat." - Ilse Fraeye, Research Group for Technology and Quality of Animal Products [6]

The potential for flavour is equally exciting. Free amino acids, which are key to the Maillard reaction, play a crucial role in creating meat's signature taste [6]. Although early prototypes have lower levels of umami precursors, such as inosine 5'-monophosphate, compared to traditional chicken [2], ongoing innovations in co-culturing techniques and optimised growth media are narrowing this gap. Importantly, Cultivated Meat naturally delivers a complete animal protein profile [4][3].

These strides in nutrition and flavour are complemented by significant regulatory advancements. With approvals already granted in the United States and Singapore [4], the technology is moving from the lab to the market. The research discussed in this article highlights how Cultivated Meat could reshape our understanding of protein quality. Its combination of nutritional depth, customisation possibilities, and economic potential positions it as a strong contender in the future of food.

If you're wondering how this innovation might soon appear on UK shelves, Cultivated Meat Shop offers an excellent resource. From product types and availability to the science driving this new category, it’s a one-stop guide to preparing for the next evolution in meat.

FAQs

How does the growth media influence the protein and amino acid profile of cultivated meat?

The growth media is a key factor in determining the protein and amino acid profile of cultivated meat. It provides the essential nutrients that cells rely on to grow and thrive. By tweaking the media's composition - like adjusting the levels of essential and non-essential amino acids, glucose, vitamins, and other components - producers can influence both the nutritional value and flavour of the final product.

Since different cell types and species process nutrients in their own unique ways, a single media formulation won't work universally for all cultivated meat products. Customising the media to suit the specific needs of the target cells allows producers to create a protein profile that mirrors conventional meat. They can even improve certain nutritional elements, giving consumers a tailored and potentially healthier option.

What makes replicating the flavour of conventional meat in cultivated meat so challenging?

Replicating the taste of cultivated meat to match that of traditional meat is no small feat. The rich flavours of conventional meat are shaped by a mix of metabolites that develop as animals grow, influenced by their diet and natural ageing processes. In contrast, cultivated meat, grown in controlled settings, often misses out on key components like free amino acids, nucleotides, and small molecules such as taurine and creatine. These elements play a crucial role in creating the savoury, umami notes that people associate with meat.

Beyond that, cultivated meat can differ in fat distribution, myoglobin levels, and the volatile aroma compounds that contribute to the roasted, meaty flavours we love when meat is cooked. Recreating the intricate balance of these factors, along with imitating the biochemical transformations that occur after harvest - like the Maillard reactions responsible for those rich, browned flavours - is a complex challenge. Overcoming these hurdles is critical for cultivated meat to deliver a taste that feels just as satisfying and familiar as its traditional counterpart.

Is cultivated meat as easy to digest as conventional meat?

Yes, cultivated meat is crafted to be as digestible as traditional meat. Research confirms it contains all the essential amino acids and achieves a protein digestibility score comparable to that of conventional animal meat. In other words, your body can absorb its nutrients just as effectively.

Studies also show that the amino acid profile of cultivated muscle cells is strikingly similar to native beef, meaning it’s biologically comparable and digested in much the same way. What’s more, cultivated meat offers the unique possibility of tailoring nutrient levels to suit specific dietary needs, making it a versatile and nutritious alternative to conventional options.